Welded Box

Reflection

This project was my second attempt at welding and I was nervous that my welds would look as terrible as the my first. But the right angle was easier to fuse together than trying to make straight lines on a flat plane. I found that welding was very zen. It goes well when find a meditative state. I chose not to polish this box because I liked the coloration and patterns that appeared in the welding process.

Blacksmithed Rose

Reflection

Though I like my rose, I would do this project again. I learned things towards the end of the process that would help me in the beginning. For example, shaping the edges of the petals more in the beginning would have helped me out at the end to get a more realistic effect.

Research paper

Ruth Asawa

Born on January 24, 1926 in Norwalk, California to Umakichi and Haru Asawa, Ruth Asawa was the middle child in a big Japanese-American family. Umakichi came to the United States as an itinerant farmer in the early 1900s with his brother. When they raised enough wealth to start a truck farming business, their family in Japan arranged marriages for them. Haru and her sister came to the United States to marry men they had only seen pictures of and start families (Cornell, 11).

Life on the farm was a practice in frugality as much as it was hard work. The children were all expected to work several hours after school. On Saturdays they could choose to go to Japanese school or work on the farm, and Ruth opted for the former. At Japanese school they learned how to speak and read Japanese as well as Japanese calligraphy and Kendo. That is where Ruth first discovered her interest in art (Cornell, 33).

When the American Naval Base at Pearl Harbor was bombed by Japanese military pilots on December 7, 1941, Ruth's life took an unexpected turn (Nakamura). Her father and uncles were arrested by the FBI in February of 1942, as many Japanese American patriarchs were, for essentially being enemy aliens (Cornell, 34). The remaining members of the family were sent to Santa Anita Assembly Center a few months later. Despite the squalid conditions of the Assembly Center, the incarcerated citizens made the most out of a bad situation. Many renowned and professional artists taught arts classes to pass the time, and Ruth met mentors that she would not have encountered if not for the incarceration (Cornell, 36.)

In September of 1942 Santa Anita was closed and the Asawas were moved to Rowher Relocation Center in Arkansas. Ruth continued her art education in the camp, using whatever materials she could find, including tin cans from the mess hall to make stamped metal art (Cornell, 36-37). In August of 1943, Ruth was able to leave the camp behind her. Though she was not permitted to return to West Coast, she was able attend Milwaukee Teacher’s College in Wisconsin (Higa, 39). She joined her sister in Mexico over summer break, and sought out working artists. She enrolled in fresco painting classes at Escuela de Pintura y Escultura and attended interior design classes at Universidad de Mexico. She studied under Clara Proset, a Cuban-born furniture designer who had studied in Germany and France and had taken a class with fellow refugee Josef Albers at Black Mountain College in North Carolina (Cornell, 14). Ruth had heard of BMC from her classmates at Milwaukee Teacher’s College, she was eager to attend. (Cornell, 43)

When she returned for her fourth year at the MTC, she was forced to leave without getting a degree. The course required her to work in a school and no school in Wisconsin would hire a Japanese American (Cornell, 15). So, having her life plans uprooted by racism again, she applied for Black Mountain College and started her education there in 1946 (Cornell, 43).

Black Mountain College was an experimental liberal arts school where students were required to work as part of their education in order to avoid the classist effects of poor students working for rich students (Cornell, 43). As a truck farmers daughter, her work ethic was well-developed and she thrived in the progressive environment. Her teachers were some of the biggest names in Modern Art, including architect Buckminster Fuller and Josef Albers, a German painter who fled the Nazi’s and was known for his work with the Bauhaus school of design (Cornell, 14, 44). Black Mountain College challenged Ruth to explore and innovate with materials and techniques. On a second summer trip to Mexico with her sister, she learned the looped wire technique for making baskets from the villagers of Toluca. She developed that technique into her signature designs. She thought of it as drawing in three dimensions. (Cornell, 14).

Ruth fell in love with an architecture student named Albert Lanier, a Georgia lawyer’s son. Despite resistance from their families, who were not comfortable with mixed-race marriages, they married and moved to San Francisco in 1949 (Harris, 52-53). The art scene in San Francisco was very interconnected and they soon became close friends with photographer, Imogen Cunningham. Despite Cunningham’s advice to make art, not babies, Ruth made both. The young couple had 6 children by 1959 (Cornell, 17). She continued to make her wire sculptures while raising her children at home. The nature of the material made this possible. It was clean, non-toxic, contained, and could be worked on in fits and starts.

In 1950 Ruth’s first wire sculpture was accepted at the San Francisco Art Association Annual at the San Francisco Museum of Art. That was the beginning of Ruth’s work being seen and collected by art collectors around the world. Throughout the 1950’s and 60’s her portfolio grew in prominence and she became a major voice in the Modern Art Movement. (Cornell, 19)

Throughout the 1970’s and 80’s, Ruth continued to innovate. She received more public art commissions including the Hyatt Hotel fountain, decorative panels for Ramada Renaissance Hotel, and Aurora Fountain (Cornell, 25-28). Finally, in 1999 she received the Bachelor of Arts degree from the Milwaukee State Teachers College that she had been denied as a student in 1946. To pile on the accolades, she received honorary doctorates from San Francisco State University and the San Francisco Art Institute and California College of the Arts. In 1982, February 12 was declared Ruth Asawa Day in San Francisco. She passed away on August 6, 2013 at the age of 87. (Wakida)

WHY?

Ruth Asawa's life was typical of a Japanese American born on the West Coast of the United States near the turn of the century, but her unique talent and extraordinary work ethic pared with a kind, likeable personality and good luck resulted in a long and successful career in the arts. As a nisei, or second generation Japanese American, she endured institutionalized racism that uprooted her life and separated her family during the incarceration of American citizens of Japanese ancestry from February 1942 until January 1945. She also benefitted from the tight knit Japanese American community of Norwalk, California and their communal efforts for educate their children in the arts and culture of Japan. Though many critics of her art attribute her style to her Japanese heritage, her work reflects the zeitgiest of American modernism as expressed through the chiasm of Black Mountain Collage in North Carolina.

That community-mindedness followed her all her career. When her children started school, she realized that art education in public schools was lacking. She founded the Alvarado Art Workshop, which became the first of many public service commitments in her life. She had been given opportunities as a child to be taught be working artists, and that was the catalyst for her creativity. She wanted that same opportunity for all children.

Asawa bucks the stereotype of the tortured, flakey artist. Though she faced difficulties and racism, she never stopped working on her art and she never stopped working for her community. When the limits of her art education butted up against the realities of science she worked with metal plating experts to develop techniques to keep her metal wire sculptures from tarnishing and to create new patina techniques. For Awasa, every challenge was an opportunity and every moment counted. In her own words, “Sculpture is like farming. If you keep at it, you can get quite a lot done.”

Figures

Untitled, 1954 (ruthasawa.com)

Untitled, 1965. (ruthasawa.com)

Andrea Fountain, 1966. (ruthasawa.com)

Notes

Cornell, Daniell, et al. The Sculpture of Ruth Asawa Contours in the Air. University of California Press, 2007.

Wakida, Patricia. Ruth Asawa. (2021, December 2). Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved 14:47, September 24, 2023 from https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Ruth%20Asawa.

Nakamura, Kelli. December 7, 1941. (2015, June 10). Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved 09:42, September 25, 2023 from https://encyclopedia.densho.org/December%207,%201941.

Niiya, Brian. "Rohwer." Densho Encyclopedia. 24 Jul 2021, 01:25 PDT. 25 Sep 2023, 10:26 <https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Rohwer>.

Ruth Asawa. “Home - Ruth Asawa.” Ruth Asawa, 31 July 2020, ruthasawa.com.

Final Project

Progress

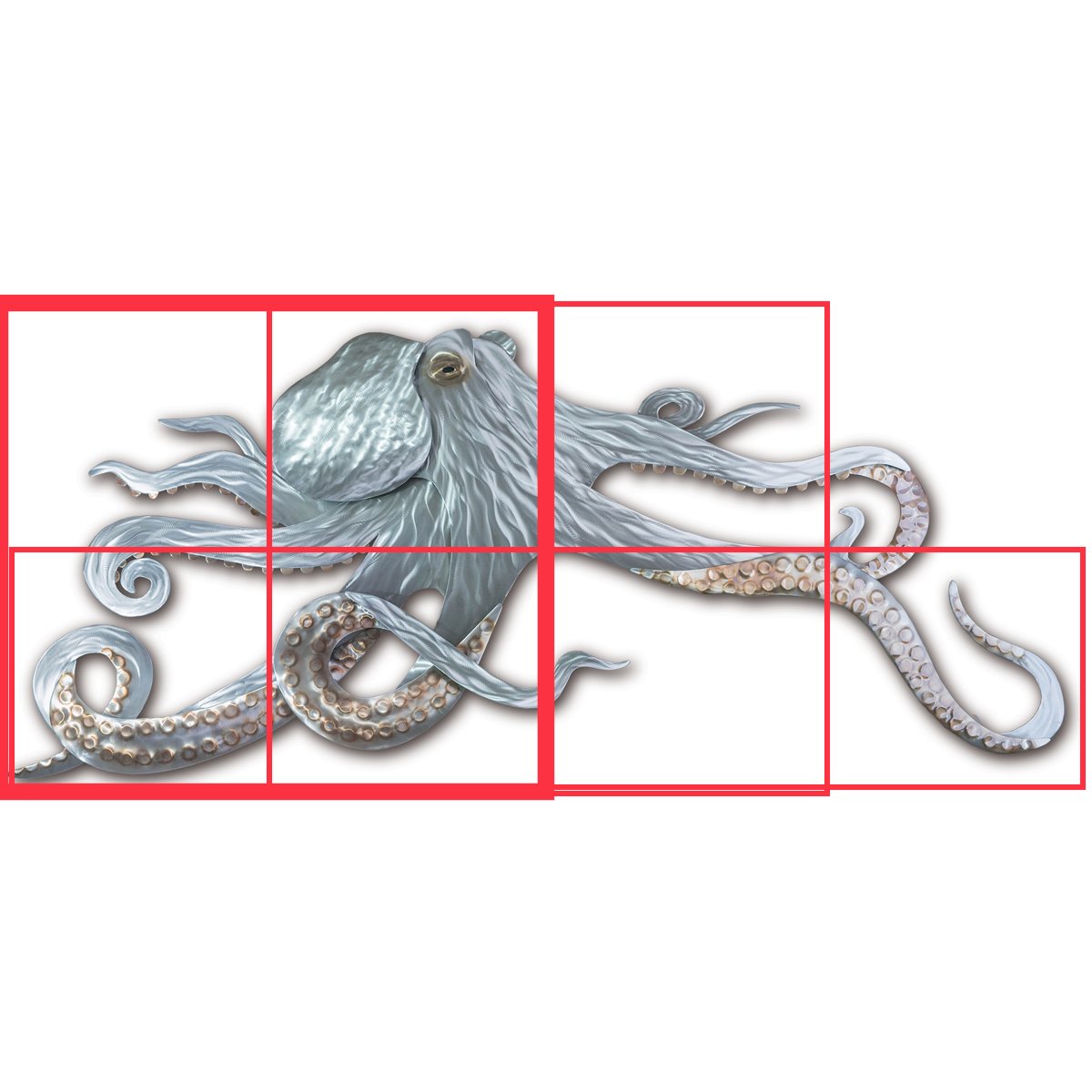

This piece of art captured the pose and level of abstraction that I wanted in my final project.

This is how my drawing came out after several rounds of drawing and cutting paper.

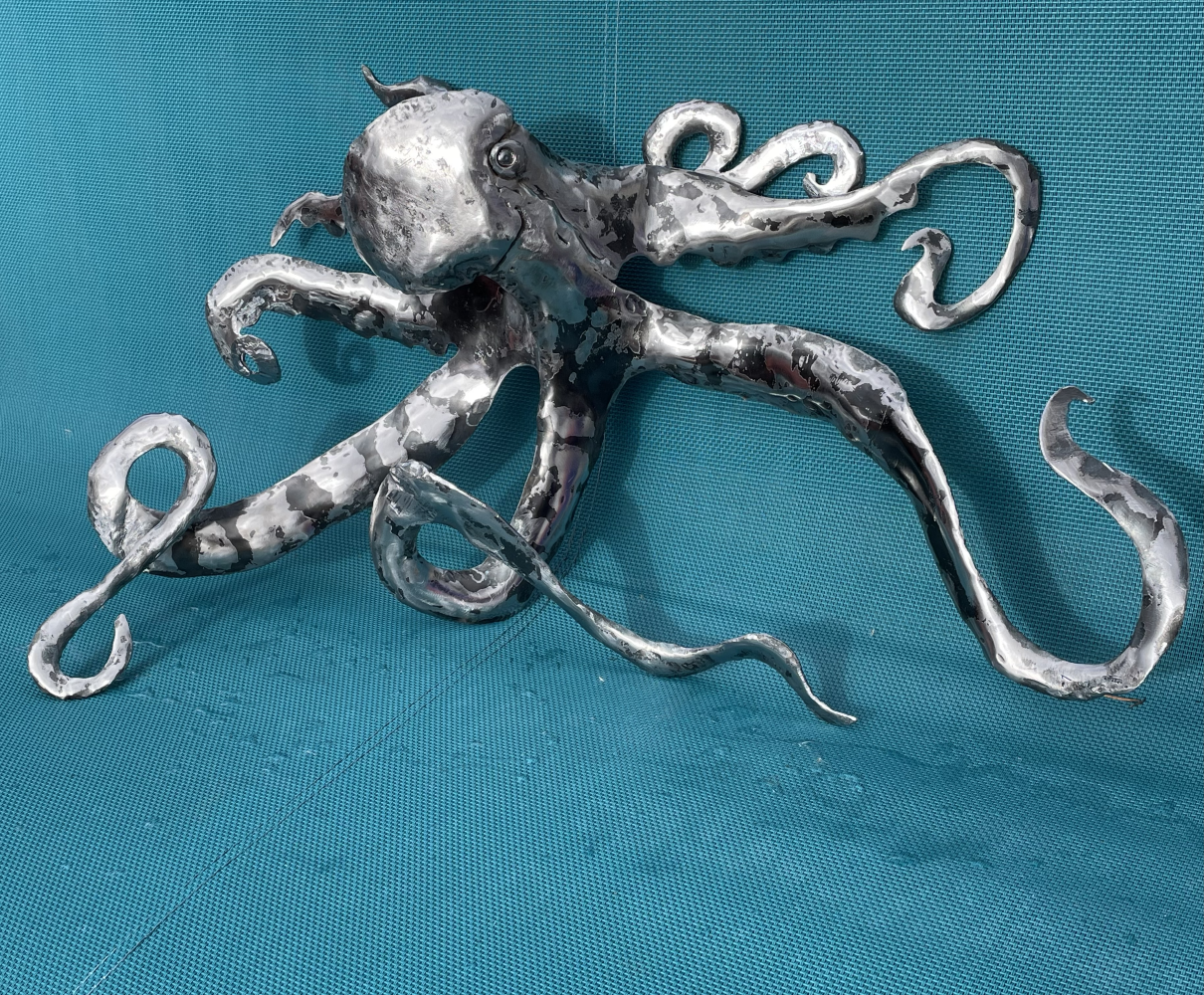

Final Product

This is the final product after many hours of blacksmithing, welding, and grinding.

The octopus installed in my living room. Otis, my dog, is not impressed.

Reflection

This project evolved as I worked on it. You can see from the inspiration image that I started out intending to make something flat. I wanted to create color and texture through heat and polishing, but I bought the wrong kind of metal. I thought I was going to make this very easy and just weld the flat shapes together, but Mr. Wheeler encouraged me to round the tentacles through blacksmithing. Though I wanted this project to be an opportunity to practice MIG welding, it turned into an opportunity to learn about grinding, buffing, and using burr tips.

I created several rounds of drawings and even created a little Sculpy model to help me realize my vision. Unfortunately, I dropped the model in the parking lot and it shattered. All of my plans were to make a 3D drawing, inspired by my research of Ruth Asawa. But if art stayed on the plan you had for it, it would be a practice in fabrication, not art. So naturally, I let my plan go.

The process of blacksmithing brought out some more interesting shapes and opportunities to correct errors in my drawing. The head part was too small and the body parts didn’t fit well. I started with broad objectives with my pieces and gradually learned how to heat and hammer with more intention. By the time I needed to fit the components together, I had the skills to make small adjustments and make a flush connection.

Welding was a much smaller part of this project than I had anticipated. MIG welding is such a fast process but I did spend more time than expected grinding my welds to create smooth transitions on the surface. The buffing process created an interesting pattern on the skin of the octopus, probably because I bought the wrong kind of metal. But I liked it so I kept it. It reminds me of tiger shark skin and octopuses are known for mimicking the patterns around them for camouflage.

Overall, I learned how to think about sculpture in a new way. Though I have experience with ceramic clay, mold making, and foundry, blacksmithing, and welding are new tools in my artistic quiver. Metal is so permanent and strong, but it can be easily shaped with heat and power tools.